Dr Nkatha Murungi

The rights of children are important and we need to ensure that there is awareness on the systems and laws that are in place to protect these civil liberties. In this piece we engage Dr Nkatha Murungi, the head of the Child and the Law Programme at the African Child Policy Forum (ACPF) to discuss the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (African Charter).

Question: What is the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child? How does it protect the rights and welfare of the child?

The African Charter is the principal legal instrument for the protection and promotion of the rights of children in Africa. It sets out the values underlying the protection of the rights and welfare of children in Africa. It looks at the entitlements of children; the responsibilities of children, and the duties of African countries to make these entitlements and protections a reality. The protections under the Charter are stronger than what is contained in other human rights instruments.

The Charter is unique in many ways, it is the only regional specific instrument on children’s rights. It embraces unique African values, such as that children not only have rights but also responsibilities.

It seeks to address issues that are prevalent in an African context, not addressed in global instruments such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child. These include harmful traditional practices, child pregnancies, apartheid, internal displacement, and education of gifted children.

The Charter establishes a monitoring body, the African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (the committee), that has a strong mandate to monitor and implement the charter. This mandate includes capacity to receive individual complaints for violations of children’s rights. Through the oversight of the Committee, the Charter goes a long way in ensuring that African countries take the necessary measures to fulfil their obligations under the Charter.

Please explain how many countries have ratified the African Charter?

Ratification means countries adopting a certain issue and signup to what Africa is saying. The overwhelming majority of African countries have ratified the African Charter. The pace of ratification and reporting on implementation has particularly improved in the past five years, partly owing to a sustained campaign by the Committee of Experts to promote ratification and reporting on the Charter.

As of 2018, at least 48 African countries have ratified the Charter. This means that only about 7 African countries are yet to ratify. These are Somalia, Central African Republic, South Sudan, Morocco, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Tunisia, and Sao Tome and Principe.

How have African countries domesticated and are implementing the African Charter?

African countries have made considerable progress towards ensuring that the rights under the Charter are implemented at the national level. This means that, not only do the countries harmonize their laws with the standards set out in the Charter, but that they also take practical steps to ensure that the laws and policies are implemented.

To ensure that steps are indeed taking steps to domesticate the Charter standards, the committee regularly engages African countries on the steps they are taking to fulfil their obligations under the Charter.

What gaps exists in African countries’ legislative frameworks, which leads to groups of children being left behind?

There are immense disparities in the adoption of legislation in Africa to give effect to the Charter. Since the Charter was adopted in 1990, most African countries have adopted a dedicated national law, or dedicated sections in general laws, to address the rights of children.

Indeed, a significant number of African countries have even recognized the rights of children in their highest laws, that is, the constitutions. However, even though these developments are very encouraging, most African countries still have immense gaps between the standards set out in their national laws, and those set out in the Charter.

There are particularly significant challenges in ensuring that African countries keep up the pace of a continuous process of law reform to ensure complete harmonization. Furthermore, most African countries lag significantly behind in ensuring that their national laws are updated to protect children from emerging challenges to the protection and wellbeing of children, such as cyber based crime and other technology based threats.

Domestication of international treaties takes more than just adopting national laws. It also requires the adoption of measures to ensure that the laws are given effect at national level.

In your expert opinion, what can be done legislatively to ensure that no child is left behind in the developmental processes?

The law is a potent tool for the protection and promotion of the rights and well-being of children in Africa. A solid legal and policy basis creates a solid foundation for demanding accountability.

One of the many challenges that African countries need to bear in mind in legislating for children in Africa, is that the law can also be an unintended barrier for children to benefit from protections that are available to everyone else in the same country.

Most of the times, laws are made in a manner that fails to recognize the peculiar needs of particularly vulnerable groups of children, such as children with disabilities, orphaned children, children living in rural areas, displaced children, or in some cases, girls.

I therefore think that it is important that law makers in African countries are conscious of the need to reflect and address the needs of all children through their legislations. By legislating on a basis of equality of all children, African countries can ensure that no child is left behind in Africa’s development.

Bio

Dr Nkatha Murungi is the Head of the Children and Law Programme at the African Child Policy Forum (ACPF). In this position, she oversees the implementation of research and advocacy work aimed at ensuring effective legal protection of children in Africa. Dr Murungi is also an advocate of the High Court of Kenya, and a lecturer and researcher in human rights with a keen focus on children, women and disability rights. She holds a Master of Laws in human rights from the University of Pretoria, and a Doctorate in Law (focusing of education of children with disabilities in Africa) from the University of the Western Cape. Her research covers a range of human rights issues including child rights, education, sexual and reproductive health rights of women and girls in Africa, disability rights, and access to justice. Before joining ACPF, Dr Murungi was a researcher in human and children’s rights in South Africa.

The Trust supports and mobilises civil society networks on issues of ending child marriage, ending violence against children, ending female genital mutilation and promoting children’s rights, to carry out advocacy and action across Africa. Special focus is placed on Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia where child marriage continues to be a problem largely driven by poverty, gender inequality, harmful traditional practices, conflict, low levels of literacy, limited opportunities for girls and weak or non-existent protective and preventive legal frameworks.

The Trust supports and mobilises civil society networks on issues of ending child marriage, ending violence against children, ending female genital mutilation and promoting children’s rights, to carry out advocacy and action across Africa. Special focus is placed on Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia where child marriage continues to be a problem largely driven by poverty, gender inequality, harmful traditional practices, conflict, low levels of literacy, limited opportunities for girls and weak or non-existent protective and preventive legal frameworks.

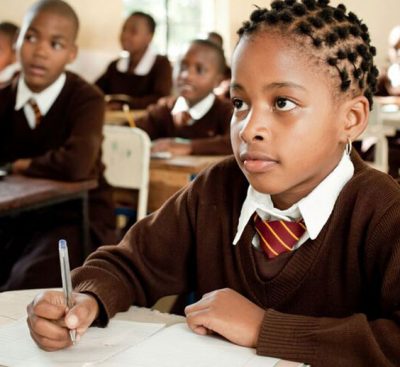

Education is a fundamental right for all children, which is also a vehicle for social, economic and political transformation in communities, countries and the African continent at large. Recent studies indicate a lack of progress in some of the critical commitments aimed at improving education quality, access, retention and achievement, particularly for girls. In most African countries, girls may face barriers to learning, especially when they reach post-primary levels of education. By implementing multi-dimensional approaches to education which includes core education, personal development, life skills and economic competencies, the Trust partners with funding partners, governments, civil societies and the private sector to improve education access.

Education is a fundamental right for all children, which is also a vehicle for social, economic and political transformation in communities, countries and the African continent at large. Recent studies indicate a lack of progress in some of the critical commitments aimed at improving education quality, access, retention and achievement, particularly for girls. In most African countries, girls may face barriers to learning, especially when they reach post-primary levels of education. By implementing multi-dimensional approaches to education which includes core education, personal development, life skills and economic competencies, the Trust partners with funding partners, governments, civil societies and the private sector to improve education access.

The Nutrition and Reproductive, Maternal, New-born, Child and Adolescent Health and Nutrition, (RMNCAH+N) of the Children’s Rights and Development Programme aims at promoting the Global Strategy for women, children and adolescents’ health within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) agenda. The strategy emphasises on the importance of effective country leadership as a common factor across countries making progress in improving the health of women, children and adolescents.

The Nutrition and Reproductive, Maternal, New-born, Child and Adolescent Health and Nutrition, (RMNCAH+N) of the Children’s Rights and Development Programme aims at promoting the Global Strategy for women, children and adolescents’ health within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) agenda. The strategy emphasises on the importance of effective country leadership as a common factor across countries making progress in improving the health of women, children and adolescents. Through its Early Childhood Development (ECD) plan, The Trust will seek to put into action the new science and evidence Report that was presented by Lancet Series on Good and early development – the right of every child. This will be achieved by mobilising like-minded partners to contribute in the new science and evidence to reach all young children with ECD. The Trust’s goal is to be a catalyst for doing things differently, in particular, to rid fragmentation and lack of coordination across ECD sectors. In response to evidence showing the importance of political will in turning the tide against the current poor access and quality of ECD. Even before conception, starting with a mother’s health and social economic conditions, the early years of a child’s life form a fundamental foundation that determines whether a child will survive and thrive optimally.

Through its Early Childhood Development (ECD) plan, The Trust will seek to put into action the new science and evidence Report that was presented by Lancet Series on Good and early development – the right of every child. This will be achieved by mobilising like-minded partners to contribute in the new science and evidence to reach all young children with ECD. The Trust’s goal is to be a catalyst for doing things differently, in particular, to rid fragmentation and lack of coordination across ECD sectors. In response to evidence showing the importance of political will in turning the tide against the current poor access and quality of ECD. Even before conception, starting with a mother’s health and social economic conditions, the early years of a child’s life form a fundamental foundation that determines whether a child will survive and thrive optimally.