Of all the suffering and abuse endured by African boys and girls – and sadly the list is long and shameful – sexual exploitation is surely one of the most egregious. In my long life I have often witnessed the worst excesses of cruelty towards children – trafficking, violence, kidnapping, forced recruitment, discrimination of all kinds – and child sexual exploitation is a red thread that runs through them all.

The statistics are truly shocking. To take just a few examples: three quarters of children living on the streets in Uganda are victims of sexual violence. More than half the children with disabilities in Cameroon and Senegal who reported sexual exploitation had been raped. In South Africa, one in three children is at risk of sexual abuse before reaching the age of 17. Nearly 40 percent of boys and girls in Ghana say they have been indecently assaulted. And so the depressing litany of abuse goes on.

However, I have no doubt that most child sexual exploitation in Africa remains hidden and unreported. One in three child victims of sexual exploitation tells no one, fearing disbelief, blame, reprisals and public shame. Boys are even less likely to report sexual abuse, a situation made worse by the absence of laws to protect them. ‘Out of sight, out of mind’ seems to be the norm.

It is no exaggeration to call child sexual exploitation in Africa a ‘silent emergency’ – the title of a new report out this week from the African Child Policy Forum which lifts the lid on the scale and scope of the problem. Child sexual exploitation is on the rise in Africa and is affecting the entire continent, fuelled by a perfect storm of opportunities for child sex offenders to thrive.

Although child sexual exploitation is by no means a 21st century phenomenon, I was disturbed to read in the report of two modern trends which exacerbate the problem: digital technology and accessible travel which enable offenders to operate both virtually and in person, with little danger of detection. Africa is fast becoming the new frontier for online child sexual abuse, especially in those countries with higher internet coverage. Yet very few countries have laws specifically criminalising online sex crimes, and those that do frequently fail to enforce them adequately.

Similarly, laws regulating travel and tourism in Africa are weak or non-existent, giving free rein to criminals intent on travelling to the continent with the sole intent of sexually exploiting children. Sex tourists – 90 percent of them men – typically originate from the USA, UK, Italy, Germany, Canada, Korea, and China. They target countries with weak or poorly-enforced laws including South Africa, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Somalia, Uganda, Tanzania, Kenya, Rwanda and Sudan.

However, we cannot blame the growth in child sexual exploitation solely on digital and travel trends. In more than four decades of working with children across the continent and beyond, I have seen time and time again the corrosive, insidious impact of poverty, inequality and discrimination driven by traditional patriarchal and cultural attitudes.

Practices such as child marriage and treating children as property – combined with outdated laws which refuse to acknowledge that boys can be victims too – have deep roots which will not be easily be changed. Attitudes that glorify predatory sexual behavior and objectify women’s sexuality have aggravated the sexual exploitation of girls, while traditional views of boys and men as perpetrators of sexual violence have led to the gross neglect of them as victims. In addition, African attitudes towards especially vulnerable groups, such as children with disabilities, those living and working on the street or those in unregulated domestic employment remain significant barriers to reducing child sexual exploitation. Homeless children, for example, almost always resort to so-called ‘survival sex’, including unprotected sex.

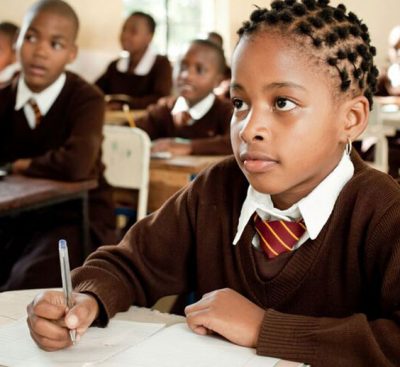

Perhaps what angers me most is that those who are supposed to protect our children – peacekeeping forces, humanitarian agencies, governments, law makers, teachers, police officers and parents – stand accused of abusing their power, control and trust in order to submit both girls and boys to sexual exploitation. It is a measure of how widespread this abuse of power has become that I was not particularly surprised to read about teachers in some west and central African countries demanding sex in exchange for higher grades. Instead of being safe havens, schools in certain instances, are becoming dangerous places for both girls and boys, who endure sexual violence from both teachers and fellow students.

The sexual exploitation of children is a multifaceted problem which requires action on multiple fronts, but that is no excuse for inaction. African governments must urgently pass legislation which is explicitly protective of the welfare and security of children, and that prohibits sexual abuse, child sex tourism and online exploitation. They must also build strong social institutions to safeguard the welfare of children as well as hold offenders accountable. Civil society organizations, teacher’s associations, parents and caregivers must also be vigorously engaged to protect children and rid our societies of this hidden scandal which is so damaging to this, and future, generations of boys and girls.

Graça Machel is a life-long campaigner for children’s rights. She is Chair of the Board of Trustees of the African Child Policy Forum, Chair of the Graça Machel Trust and a founding member of The Elders.

The Trust supports and mobilises civil society networks on issues of ending child marriage, ending violence against children, ending female genital mutilation and promoting children’s rights, to carry out advocacy and action across Africa. Special focus is placed on Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia where child marriage continues to be a problem largely driven by poverty, gender inequality, harmful traditional practices, conflict, low levels of literacy, limited opportunities for girls and weak or non-existent protective and preventive legal frameworks.

The Trust supports and mobilises civil society networks on issues of ending child marriage, ending violence against children, ending female genital mutilation and promoting children’s rights, to carry out advocacy and action across Africa. Special focus is placed on Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia where child marriage continues to be a problem largely driven by poverty, gender inequality, harmful traditional practices, conflict, low levels of literacy, limited opportunities for girls and weak or non-existent protective and preventive legal frameworks.

Education is a fundamental right for all children, which is also a vehicle for social, economic and political transformation in communities, countries and the African continent at large. Recent studies indicate a lack of progress in some of the critical commitments aimed at improving education quality, access, retention and achievement, particularly for girls. In most African countries, girls may face barriers to learning, especially when they reach post-primary levels of education. By implementing multi-dimensional approaches to education which includes core education, personal development, life skills and economic competencies, the Trust partners with funding partners, governments, civil societies and the private sector to improve education access.

Education is a fundamental right for all children, which is also a vehicle for social, economic and political transformation in communities, countries and the African continent at large. Recent studies indicate a lack of progress in some of the critical commitments aimed at improving education quality, access, retention and achievement, particularly for girls. In most African countries, girls may face barriers to learning, especially when they reach post-primary levels of education. By implementing multi-dimensional approaches to education which includes core education, personal development, life skills and economic competencies, the Trust partners with funding partners, governments, civil societies and the private sector to improve education access.

The Nutrition and Reproductive, Maternal, New-born, Child and Adolescent Health and Nutrition, (RMNCAH+N) of the Children’s Rights and Development Programme aims at promoting the Global Strategy for women, children and adolescents’ health within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) agenda. The strategy emphasises on the importance of effective country leadership as a common factor across countries making progress in improving the health of women, children and adolescents.

The Nutrition and Reproductive, Maternal, New-born, Child and Adolescent Health and Nutrition, (RMNCAH+N) of the Children’s Rights and Development Programme aims at promoting the Global Strategy for women, children and adolescents’ health within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) agenda. The strategy emphasises on the importance of effective country leadership as a common factor across countries making progress in improving the health of women, children and adolescents. Through its Early Childhood Development (ECD) plan, The Trust will seek to put into action the new science and evidence Report that was presented by Lancet Series on Good and early development – the right of every child. This will be achieved by mobilising like-minded partners to contribute in the new science and evidence to reach all young children with ECD. The Trust’s goal is to be a catalyst for doing things differently, in particular, to rid fragmentation and lack of coordination across ECD sectors. In response to evidence showing the importance of political will in turning the tide against the current poor access and quality of ECD. Even before conception, starting with a mother’s health and social economic conditions, the early years of a child’s life form a fundamental foundation that determines whether a child will survive and thrive optimally.

Through its Early Childhood Development (ECD) plan, The Trust will seek to put into action the new science and evidence Report that was presented by Lancet Series on Good and early development – the right of every child. This will be achieved by mobilising like-minded partners to contribute in the new science and evidence to reach all young children with ECD. The Trust’s goal is to be a catalyst for doing things differently, in particular, to rid fragmentation and lack of coordination across ECD sectors. In response to evidence showing the importance of political will in turning the tide against the current poor access and quality of ECD. Even before conception, starting with a mother’s health and social economic conditions, the early years of a child’s life form a fundamental foundation that determines whether a child will survive and thrive optimally.