FAO Conference

The Forty-first Session of McDougall Memorial Lecture, 22-29 June 2019, Rome

In Honour of Frank L. McDougall

Delivered by Graça Machel, Chair of the Board of the Graça Machel Trust

Thank you for the honour to address you this morning! I am not a diplomat, so I must provide a disclaimer at the outset of my remarks. You have invited a passionate humanitarian to deliver the McDougall Lecture this year and my activism, coupled with the urgent issues we face as the human family, cannot be tempered by well-mannered protocol. We do not have the luxury to be simply polite and gentle with each other. So, instead of a lecture, I propose we have a conversation this morning.

Five years ago we agreed, as a global family, to pursue the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and planet, now and into the future. It was an urgent call for action by all countries, developed and developing, in a global partnership to end poverty, to improve health and education, to reduce inequality and to spur economic growth.

The urgency, however, seems to be lost on us. I stand here with deep anguish and concern that the enthusiasm and speed with which we all agreed to work to achieve the SDGs seems to have lost steam somewhere along the way. The pace and scale with which we have been operating have not matched the magnitude of the monumental tasks and noble results we set for ourselves. Our ambition has been woefully inadequate.

I am encouraged, however, that you as FAO family have turned considerable attention this year to the intersection between migration, agriculture and rural development. And I hope this is a signal that the requisite attention and adequate investment of resources in meeting the SDGs are on the rise. We simply cannot afford not to urgently take bold action to end poverty and hunger and create more prosperous and vibrant rural communities.

Contextualizing Migration

I would like to provoke your thinking and action today by starting out with dispelling a few myths surrounding migration and I hope then to offer food for thought around how women and young women, coupled with a more innovative approach to rural development, can possibly usher us into a more well-fed, nourished, and more equitable and prosperous world.

Please allow me to challenge a few contemporary narratives that are quite damaging and untrue in our discourse around migration:

- Migration is not a new phenomenon. However; it does need to be managed adequately.

- Migration, by definition, is not harmful to countries of departure or destination.

- Turning specifically to my own continent, Africa, it is not a continent of exodus.

I begin with these points of departure to help contextualize conversations this morning.

Humanity has been on the move throughout history. We have moved across lands and seas in courageous search for new opportunities, better ways of life and improved social, political and economic conditions as well as to escape persecution, conflict and poverty.

Human beings at our core are transient and for centuries the movement of people has been happening within and between continents and countries as well as within national borders.

Global Migration

The number of migrants, thanks to innovation in travel and globalization, has increased exponentially over the past few decades. The World Economic Forum details how people today are moving more than ever before. There are presently approximately 258 million international migrants. That figure has grown rapidly since the turn of the millennium when there were 173 million.

Together with this increasing volume, we are seeing changing demographics, advancing technology, evolving needs of labour markets and continued challenges posed by conflicts, food shortages and climate change.

“There is nothing inherently wrong with migration and to treat it as a phenomenon that needs to be halted, is to deny ourselves the benefits and opportunities that come with the cross pollination of peoples and cultures.”

We sometimes think of certain countries as sources of migrants and others as recipients but most nations today, to differing degrees, experience migration from all three perspectives – as countries of origin, transit and destination.[1] Communities have played a key role in the development of sending, transit, and receiving migrants for centuries. Nowadays, international migratory pressures are more complex and globalized, and as a global family we have agreed, under the banner of SDG 10, to facilitate orderly, safe and responsible migration.

Migration and migrant labour have shaped the wealth of many nations. Surely, we must admit that the economic dominance of high-income nations like the United States and many European countries has been built on the backs of migrant labour. Migration is an integral part of the global economy and fosters growth and development through the exchanges of cultures and knowledge, as well as financial gains in the form of skills acquisition and remittances.

There is a need to have a realistic, honest examination of migration and shun the xenophobic, isolationist narratives that seem to make global news headlines on a regular basis. I know we sit here in Rome today where there are daily debates around the influx of refugees and migrants coming from Africa and the Middle East. However, I would like to paint a realistic picture based on hard facts and statistics:

When it comes to refugees, developing countries host 85 percent of the total refugee population of the world.[2] I repeat, developing countries host 85 percent of the total refugee population of the world. It is often countries with the least amount of resources that are absorbing the greatest number of refugees, and Africa plays host to the largest refugee populations in the world with over 4.4 million African refugees finding a home with their neighbours on the continent.

I must put on record that statistics from the 2019 Ibrahim Forum Report reveal African migrants represent only 14 percent of the global migrant population. This is much less than Europe which comprises 24 percent and Asia’s share which totals 41 percent of the worldwide migrant population.

To further unpack the numbers, 70 percent of sub -Saharan African migrants stay within the continent, and only 25 percent make their way to Europe.

It therefore must be clearly recognized that most refugees and migrants are settling in the global South and not flooding northern or western shores to the magnitude some would make us believe.

Rural – Urban Migration

Another aspect of the movement of people that is relevant for discussion is that of rural-to-urban migration.

Those of us gathered here today know all too well the causes and impacts of migratory patterns, the brain drain, rapid urbanization and rural flight. We are all well aware of the challenges that are associated with a lack of industrialization of agriculture, food security and investment in rural development.

So, I will not revisit an analysis of the alarming poverty statistics or belabour discourse on migratory flows which overcrowd cities and leave rural areas underdeveloped. But I will challenge us to be much bolder and more disruptive in both our planning and action to address issues of rural poverty and rural flight. Despite recycled commitments, our investment is far below the amount required to match the magnitude of these problems.

As FAO, you are uniquely positioned to contribute to the development of rural areas through the touch point of agriculture. If and when agriculture is modernized and rustic areas are brought into the 21st Century so people can benefit from electricity, water and sanitation, irrigation, quality education and gainful employment prospects, people will remain in rural communities and contribute to their vibrancy.

Nutrition and Rural Development

I would like also to emphasize the direct linkage between hunger and migration. As you know, in 2018 more than 113 million people across 53 countries in the world experienced acute hunger requiring urgent food, nutrition and livelihood assistance. Many of those suffering from acute hunger became migrants due to fleeing protracted conflicts or extreme weather conditions in the search of food for their families and the basics of survival.

This type of forced migration disrupts rural livelihoods and threatens food security and nutrition in areas of both origin and destination. I must make specific mention of the importance of nutrition here.

“A lack of adequate nutrition is a key contributor to unacceptably high levels of both maternal and child mortality as well as stunting– and therefore to the loss of human capital for the overall economic, social and political development.”

Studies[3] in several African countries reveal that the cost of malnutrition has a huge impact on a country’s economic growth. The knock-on effects of stunting on learning and on earning, is quite debilitating when translated into economic terms. For example, losses in GDP are estimated at 10 percent in Malawi, 11.5 percent in Rwanda and 16.5 percent in Ethiopia. This is economic loss.

As such, adequate nutrition, is a critical element of national development, and as the FAO, I encourage you to adequately focus and prioritize promoting nutrient rich food production and food security as there is clear evidence of its well‑being to individuals, households, and the vibrancy of national economies.

Crop yields and growing seasons are being adversely impacted by climate change. For example, hunger already affects about 240 million Africans daily. Recent estimates indicate that by 2050, even a change of approximately 1.2 to 1.9 degrees Celsius will have increased the number of Africa’s undernourished from 25 percent to 95 percent. Decreasing crop yields and increasing population will put additional pressure on an already fragile food production system. If the current situation persists, Africa will be fulfilling only 13 percent of its food needs by 2050. This situation will further threaten about 65 percent of African workers who depend on agriculture for their livelihoods including children and the elderly, who are particularly vulnerable to food insecurity.[4] We know this fate is upon us—but this doesn’t have to become our destiny. We have the power to reverse it. Starting now!

“I ask you as experts: what innovative instruments and climate smart policies are we putting in place now to avert this impending crisis?”

Innovation in Rural Development

Innovation in agriculture needs to cut across all dimensions of the production cycle along the entire value chain – from crop, forestry, fisheries and livestock production to the management of inputs and resources to market access. However, I challenge us this morning to go beyond incremental changes and small-scale innovative initiatives. I challenge you, really, to disrupt the agricultural sector as a whole!

Like Uber has transformed the transportation business and like Netflix has shaken the entertainment industry, we need a game changer for the agricultural sector. Within the UN family you have researchers and scientists from all fields of study, world class agronomists and policy experts, and pools of talented young people from around the world at your disposal. Please harness their creativity and expertise, and leapfrog over the traditional! Push the boundaries of our current thinking and approaches.

For example:

How big are the investments we are making in climate‑resilient agriculture approaches that place value on indigenous seed production as well as traditional know-how around nutrient-rich crop diversification and farming and animal husbandry techniques?

How can we democratize technology? There are places where innovative techniques such as drip irrigation and solar powered desalination systems are transforming patches of deserts into vibrant farmlands. All this innovation is happening while in other parts of the world, people are still languishing in hostile environments, and are food and livelihood insecure. We need to massively scale up successful approaches and implement best practices so that our advances in technology benefit millions and not just a few hundred thousand.

And how do we better leverage the blue economy and potentially transformative industry of aquaculture? Over 70 percent of the planet is made up of aquatic systems that play a crucial, growing, and yet largely underutilized role in food and livelihood security and nutrition from the fisheries and aquaculture sectors.

Fish is more than food; it is a source of income, trade, and in coastal communities it is a way of life. More than three billion people rely on fish for animal protein, and more than 800 million people, 10 percent of the world’s population, derive their livelihoods from aquaculture, fisheries and associated fish value chains. Invest massively in this industry to tap into its potential to advance rural development, and tackle hunger and malnutrition.

“How can we scale the uptake of new farming systems such as vertical farming and tech innovations to traditional greenhouses?”

I know I have more questions than solutions, but I hope to be able to ignite a fire of creative action in this room this morning to find their answers. As a women’s rights activist, I would be neglectful of my duties, if I did not bring to your attention the obvious fact that girls and women are overlooked, yet critical success factors to rural development.

The Girl – Child as A Change Agent

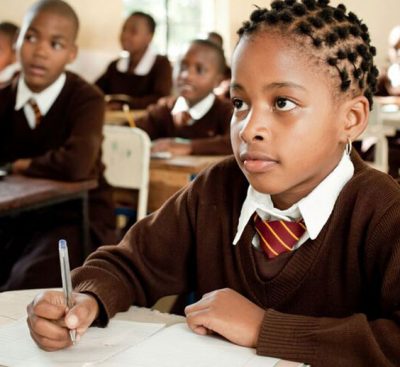

Investing in the education of the girl child, in particular in rural areas, is a strategic entry point to transform a whole range of societal norms and traditional practices to create communities that value and protect the rights of women.

A study by UNICEF shows that women and girls in sub-Saharan Africa collectively spend about 40 billion hours a year collecting water. Wouldn’t these billions of hours be better applied towards skills development? Shouldn’t we be equipping our girls in the STEM fields and ensuring they receive a diversity of skills to meet the demands of the agriculture sector as well as industrialized labour markets? We owe it to our children to work much more quickly and smarter, and in concert with each other as the UN family to figure out ways to better educate, feed, and provide a solid foundation for our youngest generations to flourish.

“A lack of access to education for women is one of the most significant barriers that hinder enhancing skills that will allow them economic freedom. Investment in the girl child equips her to realize her personal aspirations and professional ambitions, and provides her with the proper footing to contribute her full potential to the betterment of her community—whether it rural or urban.”

Women as Change Agents of Agricultural Development

Studies tell us that today there are nearly 821 million people who are undernourished, and if we are to end hunger by 2030, we must address the inequalities between women and men in agriculture. Women comprise more than 50 percent of the agricultural workforce in developing countries, and in some regions of the world, such as my own, they comprise 70 percent of the rural workforce.

Yet, they receive only a fraction of the land, credit, inputs such as improved seeds and fertilizers, agricultural training and information compared to men. Rural women, in particular, should be recognized and valued as major agents of change in agriculture development.

As farmers and farm workers, horticulturists and market sellers, businesswomen, entrepreneurs and community leaders, they fulfil important roles throughout agri-food value chains, as well as in the management of natural resources such as land and water.

Yet the gender gap in food and agriculture is extensive. Women are under-represented in local institutions and governance mechanisms, and tend to have less decision-making power. In addition to these constraints, prevailing gender norms and discrimination often mean that women face an excessive work burden, and that much of their labour remains unpaid and unrecognized.

“Bridging this gender yield gap would boost food and nutrition security globally. Studies project this additional yield could reduce the number of undernourished people in the world by over 100 million.”

Because women are such central players in the food chain and key to agricultural output globally, it is imperative that institutions focus on innovative ways to advance women’s contributions in this sector. I offer a few examples:

Women need to be in the forefront of agricultural industrialization, at the decision-making table and throughout the value chain, including in the development of better farming technologies as women in Africa and Asia are still using a farming hoe. I repeat, in Africa and Asia women are still using a farming hoe, in a world where there is new tech-savvy farming equipment easing the physical burden of farming and increasing productivity in other parts of the world. Asian and African women often undertake the arduous task of chopping firewood and suffer from smoke inhalation to cook for their families. When there are climate-friendly stoves within our reach to provide to them, this level of physical exertion and reduction of quality of life is simply unacceptable.

Women are often the custodians of treasured traditions and know-how. The sharing of their knowledge as well as value of indigenous seeds and cultivation of nutrient-rich crops needs to be recognized and scaled up. Governments need to scrap the traditional, social and legislative shackles which limit women from exercising their right to land ownership. The securing of land and land rights for women needs to have a set time period in which they will be realized.

“Women need to be equipped with the knowledge and skills to upscale their SMEs as entrepreneurs, and valued for their contribution to the economy.”

It is utterly difficult to comprehend that we have not grasped the fact that we place a stranglehold on our own growth by limiting the potential of half of our population. The disenfranchisement of women is not only an economic issue, but a question of equality and social justice. The agricultural sector is one obvious industry where it is an absolute must to capitalize on the vital role women already play.

In addition to my advocacy for the increased investment in the girl child and women, I will close by briefly touching on the influential role of youth in the equation of migration and rural development.

Youth and Rural Development

Africa provides to the world a unique laboratory for how to manage the demographic dividend. The 2019 Ibrahim Forum report tells us that the agriculture sector accounts for up to 60% of African jobs and roughly one third of the continent’s GDP.

According to the Afrobarometer survey data from 34 African countries, agriculture employs nearly 19 percent of working young Africans aged 18-35, and is the biggest job-generating sector for young people. However, in rural areas, the lack of decent work opportunities is among the principal drivers of rural to urban migration, especially for youth.

Agriculture is expected to remain the main pool of employment opportunities for sub-Saharan African youth in the foreseeable future. Despite this, for the majority, agriculture is often seen as outdated, unprofitable and hard work for the uneducated in many settings across the globe. Given these dynamics, agriculture must become appealing! Strategic investments to modernize the sector and rural areas must be applied to both attract and retain young people so they feel it is an opportunity-rich environment where they can realize their aspirations without having to migrate elsewhere.

In addition to the structural changes and disruptions I advocated for earlier, in the immediate term, many simple technologies can solve some of the major challenges currently faced by farmers and young agriculture entrepreneurs in the world. For instance access to markets, access to updated technologies and research, knowledge of commodity prices and early warning systems on weather and pests, to name just a few.

Two examples I will share emerging from Africa are “Gro Intelligence” and “Wefarm” – these two initiatives are leveraging technology and the talents of young people that could be scaled globally.

Conclusion

Our problems persist because we are sitting in our comfort zones and not challenging ourselves individually and institutionally to change the status quo. There has been a shameful failure of global governance to address issues of food security, forced migration and equitable economic development. There is a dismal disregard for accountability and responsibility taken by those with decision‑making powers to transform broken systems which lead to economic and social inequality.

We do make very good statements. We adopt very good policies but when it comes to implementation and accountability, we are failing in a dismal way.

There is also a failure of governance at the country level to set priorities right. Governments are not allocating sufficient energy or resources to address the root causes of poverty and provide all their citizens with a sound quality of life.

And lastly, there is a failure of individual conscience. A heartless complacency with the status quo has given birth to a bankruptcy of human solidarity.

As I stand here this morning, every minute children are dying in Africa and Asia from malnutrition.

As I stand here, you made a mistake inviting an activist…

“I will ask you to do one simple thing. Imagine you have in front of you your grandchild, your own grandchild who is dying of hunger. Simply hunger. What would you do?”

Suppose and remember any one of us today, we are going to have three meals and three meals of which we are going to choose what we want to eat. Yet, as I’m saying, there are children who would be saved by just one loaf of bread and clean water. There are mothers and grandmothers like me who are burying their babies simply because we did not help them to use their power to protect their children.

I want to say those children, those millions of children, are dear to a mother, to a father, to a grandfather, exactly as our own grandchildren are dear to us.

There are no rights. There is no right that will continue to live in a world as if these things which are happening are normal. They are not normal. They are man-made and what I want to say is that it is our responsibility, each one of you here, including myself, are responsible, and that is what I call conscience; to know it is my responsibility, not anybody else’s.

A loss of a child to any one of us would touch you, touch your heart, and for women, it would also touch your womb. But because it is another person’s child, we live as if it is not our business. And I want to challenge you. It is your business. It is my business. It is our collective business. We cannot be proud of ourselves in the 21st Century, to allow these millions of children to continue to die, as if we do not have the knowledge, we do not have the capacity, we do not have even the means to communicate quickly and to resolve this problem. It is a shame on each one of us if this does not change.

“But I want to finish by saying, we are left only with ten years for these SDGs. Only ten. So, it is not too long. If we do not really change the way we do business, then we will come in ten years time and say: “Oh no, we did our best but we failed.”

Again, I want to come to your own grandchildren. How do you look into the eyes of your child when you fail on your promise? When you say something and you come later to recognize that you lied to your own grandchild. We promised those children in 2015 that we will end hunger, and they will look into our eyes and say, why did you lie to us?

That is why I was saying inviting an activist was perhaps not a good idea. And I want to say I recognize that you are working hard. I am not saying you are not working. What I am saying is that collectively whatever we have been doing so far, is not good enough. That is what we have to recognize. It is not like we are not working, but it is not good enough. Because the results are not matching what we have set out to do.

So, the point is, how do we close the gap between what we promised and the outcomes and the results of what we are doing? And we have only ten years because we promised it will be overcome. And we did not say we will reduce, like with the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). We said we are going to end hunger, So, I am sorry, you have to scale up.

I am terribly sorry, you have to scale up.

You have massively to reverse the priorities of investment and food for everyone on this globe. It can be achieved. Then you can come to me as activists. I will talk to women, yes. I will talk to youth. Give me the tools. I am not saying you do it alone. Let us do it together. But we definitely have to change the way we do things and we have to scale up much more.

[1] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/01/global-migration-can-be-a-success/

[2] Source: GEMR/UNHCR Global Trends 2017

[3] https://www1.wfp.org/news/new-study-reveals-huge-impact-hunger-economy-malawi-0

[4] Africa Renewal. (2014). Despite climate change, Africa can feed Africa By: Richard Munang and Jesica Andrews. https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/special-edition-agriculture-2014/despite-climate-change-africa-can-feed-africa

The Trust supports and mobilises civil society networks on issues of ending child marriage, ending violence against children, ending female genital mutilation and promoting children’s rights, to carry out advocacy and action across Africa. Special focus is placed on Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia where child marriage continues to be a problem largely driven by poverty, gender inequality, harmful traditional practices, conflict, low levels of literacy, limited opportunities for girls and weak or non-existent protective and preventive legal frameworks.

The Trust supports and mobilises civil society networks on issues of ending child marriage, ending violence against children, ending female genital mutilation and promoting children’s rights, to carry out advocacy and action across Africa. Special focus is placed on Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia where child marriage continues to be a problem largely driven by poverty, gender inequality, harmful traditional practices, conflict, low levels of literacy, limited opportunities for girls and weak or non-existent protective and preventive legal frameworks.

Education is a fundamental right for all children, which is also a vehicle for social, economic and political transformation in communities, countries and the African continent at large. Recent studies indicate a lack of progress in some of the critical commitments aimed at improving education quality, access, retention and achievement, particularly for girls. In most African countries, girls may face barriers to learning, especially when they reach post-primary levels of education. By implementing multi-dimensional approaches to education which includes core education, personal development, life skills and economic competencies, the Trust partners with funding partners, governments, civil societies and the private sector to improve education access.

Education is a fundamental right for all children, which is also a vehicle for social, economic and political transformation in communities, countries and the African continent at large. Recent studies indicate a lack of progress in some of the critical commitments aimed at improving education quality, access, retention and achievement, particularly for girls. In most African countries, girls may face barriers to learning, especially when they reach post-primary levels of education. By implementing multi-dimensional approaches to education which includes core education, personal development, life skills and economic competencies, the Trust partners with funding partners, governments, civil societies and the private sector to improve education access.

The Nutrition and Reproductive, Maternal, New-born, Child and Adolescent Health and Nutrition, (RMNCAH+N) of the Children’s Rights and Development Programme aims at promoting the Global Strategy for women, children and adolescents’ health within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) agenda. The strategy emphasises on the importance of effective country leadership as a common factor across countries making progress in improving the health of women, children and adolescents.

The Nutrition and Reproductive, Maternal, New-born, Child and Adolescent Health and Nutrition, (RMNCAH+N) of the Children’s Rights and Development Programme aims at promoting the Global Strategy for women, children and adolescents’ health within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) agenda. The strategy emphasises on the importance of effective country leadership as a common factor across countries making progress in improving the health of women, children and adolescents. Through its Early Childhood Development (ECD) plan, The Trust will seek to put into action the new science and evidence Report that was presented by Lancet Series on Good and early development – the right of every child. This will be achieved by mobilising like-minded partners to contribute in the new science and evidence to reach all young children with ECD. The Trust’s goal is to be a catalyst for doing things differently, in particular, to rid fragmentation and lack of coordination across ECD sectors. In response to evidence showing the importance of political will in turning the tide against the current poor access and quality of ECD. Even before conception, starting with a mother’s health and social economic conditions, the early years of a child’s life form a fundamental foundation that determines whether a child will survive and thrive optimally.

Through its Early Childhood Development (ECD) plan, The Trust will seek to put into action the new science and evidence Report that was presented by Lancet Series on Good and early development – the right of every child. This will be achieved by mobilising like-minded partners to contribute in the new science and evidence to reach all young children with ECD. The Trust’s goal is to be a catalyst for doing things differently, in particular, to rid fragmentation and lack of coordination across ECD sectors. In response to evidence showing the importance of political will in turning the tide against the current poor access and quality of ECD. Even before conception, starting with a mother’s health and social economic conditions, the early years of a child’s life form a fundamental foundation that determines whether a child will survive and thrive optimally.