Hunger is the single most acute problem facing Africa’s children. As you read this, around sixty million children across Africa suffer from hunger. Not the mildly uncomfortable sort of hunger that comes from skipping the odd meal, but permanent, relentless malnourishment, stunting and wasting.

No child should go hungry. I find it utterly unacceptable that lack of decent food is still killing African children on such a vast scale in the 21st century, yet the statistics are depressingly familiar. Hunger is a factor in nearly half of all child deaths in Africa. Nine out of ten African children do not eat the minimum amount of food with the desired degree of frequency. One in three is stunted. Two out of five do not get regular meals. One third of child deaths can be traced to micronutrient deficiencies.

I will join political leaders and child rights experts in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, on May 23-24 2019 to try and find a way out of Africa’s child hunger problems. At the Eighth International Policy Conference on the African Child, delegates will hear about the urgency of addressing child hunger and the need to develop and implement appropriate policies and programmes.

To those of us who campaign for child rights, the causes of Africa’s seemingly intractable child hunger challenge are well known. Child hunger is driven by poverty and gender inequality – children from poor and rural backgrounds suffer the most from hunger, and women and girls are disproportionately affected. In some countries, stunting rates are twice as high among rural children as among their urban counterparts.

Added to this, the continent’s food system is broken. Increased food production has not resulted in better diets for children. Supply chains are unfit for serving rapidly expanding urban populations as well as the rural poor. Agricultural production, driven by economic growth targets, encourages the production of major cereal crops instead of more nutritious foods such as pulses, fruit and vegetables.

The problem is further compounded by widespread government failures to ensure the rights of children to food. In 2015, African countries committed to a ten-year African Regional Nutrition Strategy, yet half of them are currently off course to meet their targets. Eight countries are off course to meet childhood wasting targets, and only two countries are likely to meet the stunting targets.

Climate change and conflict also have a significant impact. Three-quarters of all stunted children under the age of five live in conflict zones. In 2017, armed conflict was the biggest single cause of acute food insecurity in 18 countries, leading to nearly 74 million people needing urgent assistance. In the same year tropical storms, droughts and flooding caused food insecurity for more than 21 million people in Ethiopia, Malawi, Zimbabwe and Kenya.

I strongly believe that child hunger is fundamentally a political problem, the offspring of an unholy alliance of political indifference, unaccountable governance and economic mismanagement. Persistent and naked though the reality is, it remains a silent tragedy, one that remains largely unacknowledged and tolerated, perhaps because it is a poor person’s problem.

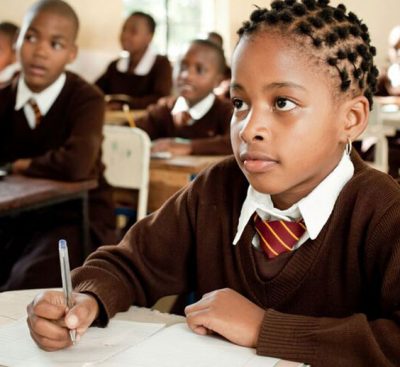

Hunger has devastating consequences. I have seen for myself how hungry children perform less well in school and suffer from low self-esteem. They are less healthy and productive, earning less as adults than their peers. The human and social impact of hunger is clear, but less well known are the huge economic costs. Hunger costs African countries as much as 17 percent of their GDP and threatens their future development.

I will reiterate what I said in November 2018 at the African Development Bank’s Eminent Speakers 2018 Lecture Series: “the lasting effects [of stunting] on the cognitive and physical development of the African child and their families has led to the stunted development of societies”. Ensuring that children have enough good food is the best investment Africa can make to build its human capital and assure its economic future.

Graça Machel is a world renowned women’s and child rights’ campaigner. She is Founder of the Graça Machel Trust, a member of The Elders, and Chair of the International Board of Trustees of the Africa Child Policy Forum (ACPF).

The Trust supports and mobilises civil society networks on issues of ending child marriage, ending violence against children, ending female genital mutilation and promoting children’s rights, to carry out advocacy and action across Africa. Special focus is placed on Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia where child marriage continues to be a problem largely driven by poverty, gender inequality, harmful traditional practices, conflict, low levels of literacy, limited opportunities for girls and weak or non-existent protective and preventive legal frameworks.

The Trust supports and mobilises civil society networks on issues of ending child marriage, ending violence against children, ending female genital mutilation and promoting children’s rights, to carry out advocacy and action across Africa. Special focus is placed on Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia where child marriage continues to be a problem largely driven by poverty, gender inequality, harmful traditional practices, conflict, low levels of literacy, limited opportunities for girls and weak or non-existent protective and preventive legal frameworks.

Education is a fundamental right for all children, which is also a vehicle for social, economic and political transformation in communities, countries and the African continent at large. Recent studies indicate a lack of progress in some of the critical commitments aimed at improving education quality, access, retention and achievement, particularly for girls. In most African countries, girls may face barriers to learning, especially when they reach post-primary levels of education. By implementing multi-dimensional approaches to education which includes core education, personal development, life skills and economic competencies, the Trust partners with funding partners, governments, civil societies and the private sector to improve education access.

Education is a fundamental right for all children, which is also a vehicle for social, economic and political transformation in communities, countries and the African continent at large. Recent studies indicate a lack of progress in some of the critical commitments aimed at improving education quality, access, retention and achievement, particularly for girls. In most African countries, girls may face barriers to learning, especially when they reach post-primary levels of education. By implementing multi-dimensional approaches to education which includes core education, personal development, life skills and economic competencies, the Trust partners with funding partners, governments, civil societies and the private sector to improve education access.

The Nutrition and Reproductive, Maternal, New-born, Child and Adolescent Health and Nutrition, (RMNCAH+N) of the Children’s Rights and Development Programme aims at promoting the Global Strategy for women, children and adolescents’ health within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) agenda. The strategy emphasises on the importance of effective country leadership as a common factor across countries making progress in improving the health of women, children and adolescents.

The Nutrition and Reproductive, Maternal, New-born, Child and Adolescent Health and Nutrition, (RMNCAH+N) of the Children’s Rights and Development Programme aims at promoting the Global Strategy for women, children and adolescents’ health within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) agenda. The strategy emphasises on the importance of effective country leadership as a common factor across countries making progress in improving the health of women, children and adolescents. Through its Early Childhood Development (ECD) plan, The Trust will seek to put into action the new science and evidence Report that was presented by Lancet Series on Good and early development – the right of every child. This will be achieved by mobilising like-minded partners to contribute in the new science and evidence to reach all young children with ECD. The Trust’s goal is to be a catalyst for doing things differently, in particular, to rid fragmentation and lack of coordination across ECD sectors. In response to evidence showing the importance of political will in turning the tide against the current poor access and quality of ECD. Even before conception, starting with a mother’s health and social economic conditions, the early years of a child’s life form a fundamental foundation that determines whether a child will survive and thrive optimally.

Through its Early Childhood Development (ECD) plan, The Trust will seek to put into action the new science and evidence Report that was presented by Lancet Series on Good and early development – the right of every child. This will be achieved by mobilising like-minded partners to contribute in the new science and evidence to reach all young children with ECD. The Trust’s goal is to be a catalyst for doing things differently, in particular, to rid fragmentation and lack of coordination across ECD sectors. In response to evidence showing the importance of political will in turning the tide against the current poor access and quality of ECD. Even before conception, starting with a mother’s health and social economic conditions, the early years of a child’s life form a fundamental foundation that determines whether a child will survive and thrive optimally.