Graça Machel, Founder, Graça Machel Trust

“All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” These simple but powerful words are the first line of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted by the United Nations at an extraordinary meeting in London seventy years ago, in 1948.

But do they mean anything today for a child in Yemen whose school has been bombed, or a rape survivor in South Sudan, or dissidents in Russia or Saudi Arabia living in fear of abduction and assassination?

And what do they offer for the next generation of leaders, who see many people currently in power in their countries downgrading or demeaning the importance of human rights as national and international politics are increasingly driven by polarisation and populism?

I believe the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is a critical moment to reaffirm its values and guarantee its continued relevance.

This means engaging global citizens, listening to the victims of human rights abuses and advocating policies that protect their rights by holding leaders to account.

This week, I will join three former UN High Commissioners for Human Rights – Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein, who left his post in August 2018, Mary Robinson and Louise Arbour – in a debate at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) on the challenges facing human rights leadership today.

We will be joined by my fellow members of The Elders – the group of independent leaders founded by my late husband Nelson Mandela – and young leaders brought together from around the world by the British Council.

Their voices and perspectives are crucial to ensure that the Declaration remains a living text that responds to changing social norms, attitudes and laws regarding gender, sexuality, race and multicultural identity.

From Palestine to the Central African Republic, Eritrea to Myanmar, and Venezuela to the Syria, countless women, men and children have their human rights denied and are subject to arbitrary detention, torture, sexual assault and even assassination.

Tyrants and dictators are further emboldened when democratic leaders abjure their responsibilities to uphold human rights and international law, in favour of either cynical isolationism or cowardly short-termism.

The endemic lack of trust in public institutions we have observed in the decade since the global financial crisis means there is a very real threat of human rights are being overturned, as those who supposedly speak for the people see them as an impediment to their grip on power and personal enrichment.

Understanding the historical context behind the Declaration’s genesis, in all its complexity, is essential to preserving its legacy and guaranteeing its endurance.

It was born out of the devastation of the Second World War, the atrocity of the Holocaust and the determination – as seen in the contemporaneous Nuremburg Trials – to create new instruments to deliver justice and protect rights and freedoms. Above all the Declaration is a global text, informed by the French Revolution’s Declaration of the Rights of Man as well as the African notion of “Ubuntu” – eloquently explained by Archbishop Desmond Tutu as meaning “my humanity is inextricably bound up in yours.”

However, its power has always depended on the political will of leaders to uphold, and not just pay hypocritical lip-service to its noble aspirations.

The past seven decades offer countless depressing examples of the latter.

In the same year the Declaration was signed, South Africa started the process of codifying their brutal apartheid regime; Palestinians were dispossessed en masse in the “nakba” linked to the founding of the State of Israel; and Britain and France were engaged in military conflicts around the globe to try to preserve their colonial empires.

To paraphrase George Orwell, many of the leaders who signed the Declaration in 1948 clearly felt that “all humans’ rights are equal, but some are more equal than others”.

Human rights for the victims of colonialism, racism and other forms of discrimination, from sexism and homophobia to structural impoverishment and class prejudice, have only ever been won by the struggle of brave activists at the grassroots.

This was the path taken by Nelson Mandela, who fought all his life to secure freedom and justice in South Africa. Twenty years ago, he addressed the UN General Assembly to mark the 50th anniversary of the Declaration. Whilst hailing the power of its words, he challenged his fellow world leaders that the “failure to achieve this vision… results from the acts of commission and omission, particularly by those who occupy positions of leadership in politics and the economy.”

His words still ring true down the years, and should inspire all of us to hold our leaders to account, and take responsibility for our own actions as global citizens.

Together, I remain convinced that we can deliver the freedom at the heart of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, both today and for future generations.

The Trust supports and mobilises civil society networks on issues of ending child marriage, ending violence against children, ending female genital mutilation and promoting children’s rights, to carry out advocacy and action across Africa. Special focus is placed on Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia where child marriage continues to be a problem largely driven by poverty, gender inequality, harmful traditional practices, conflict, low levels of literacy, limited opportunities for girls and weak or non-existent protective and preventive legal frameworks.

The Trust supports and mobilises civil society networks on issues of ending child marriage, ending violence against children, ending female genital mutilation and promoting children’s rights, to carry out advocacy and action across Africa. Special focus is placed on Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia where child marriage continues to be a problem largely driven by poverty, gender inequality, harmful traditional practices, conflict, low levels of literacy, limited opportunities for girls and weak or non-existent protective and preventive legal frameworks.

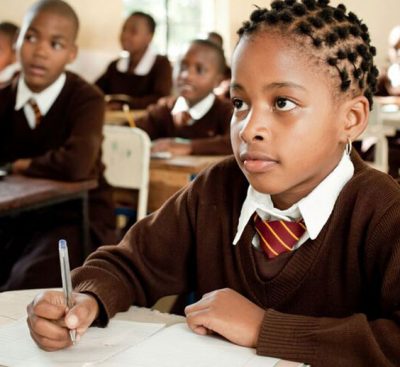

Education is a fundamental right for all children, which is also a vehicle for social, economic and political transformation in communities, countries and the African continent at large. Recent studies indicate a lack of progress in some of the critical commitments aimed at improving education quality, access, retention and achievement, particularly for girls. In most African countries, girls may face barriers to learning, especially when they reach post-primary levels of education. By implementing multi-dimensional approaches to education which includes core education, personal development, life skills and economic competencies, the Trust partners with funding partners, governments, civil societies and the private sector to improve education access.

Education is a fundamental right for all children, which is also a vehicle for social, economic and political transformation in communities, countries and the African continent at large. Recent studies indicate a lack of progress in some of the critical commitments aimed at improving education quality, access, retention and achievement, particularly for girls. In most African countries, girls may face barriers to learning, especially when they reach post-primary levels of education. By implementing multi-dimensional approaches to education which includes core education, personal development, life skills and economic competencies, the Trust partners with funding partners, governments, civil societies and the private sector to improve education access.

The Nutrition and Reproductive, Maternal, New-born, Child and Adolescent Health and Nutrition, (RMNCAH+N) of the Children’s Rights and Development Programme aims at promoting the Global Strategy for women, children and adolescents’ health within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) agenda. The strategy emphasises on the importance of effective country leadership as a common factor across countries making progress in improving the health of women, children and adolescents.

The Nutrition and Reproductive, Maternal, New-born, Child and Adolescent Health and Nutrition, (RMNCAH+N) of the Children’s Rights and Development Programme aims at promoting the Global Strategy for women, children and adolescents’ health within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) agenda. The strategy emphasises on the importance of effective country leadership as a common factor across countries making progress in improving the health of women, children and adolescents. Through its Early Childhood Development (ECD) plan, The Trust will seek to put into action the new science and evidence Report that was presented by Lancet Series on Good and early development – the right of every child. This will be achieved by mobilising like-minded partners to contribute in the new science and evidence to reach all young children with ECD. The Trust’s goal is to be a catalyst for doing things differently, in particular, to rid fragmentation and lack of coordination across ECD sectors. In response to evidence showing the importance of political will in turning the tide against the current poor access and quality of ECD. Even before conception, starting with a mother’s health and social economic conditions, the early years of a child’s life form a fundamental foundation that determines whether a child will survive and thrive optimally.

Through its Early Childhood Development (ECD) plan, The Trust will seek to put into action the new science and evidence Report that was presented by Lancet Series on Good and early development – the right of every child. This will be achieved by mobilising like-minded partners to contribute in the new science and evidence to reach all young children with ECD. The Trust’s goal is to be a catalyst for doing things differently, in particular, to rid fragmentation and lack of coordination across ECD sectors. In response to evidence showing the importance of political will in turning the tide against the current poor access and quality of ECD. Even before conception, starting with a mother’s health and social economic conditions, the early years of a child’s life form a fundamental foundation that determines whether a child will survive and thrive optimally.